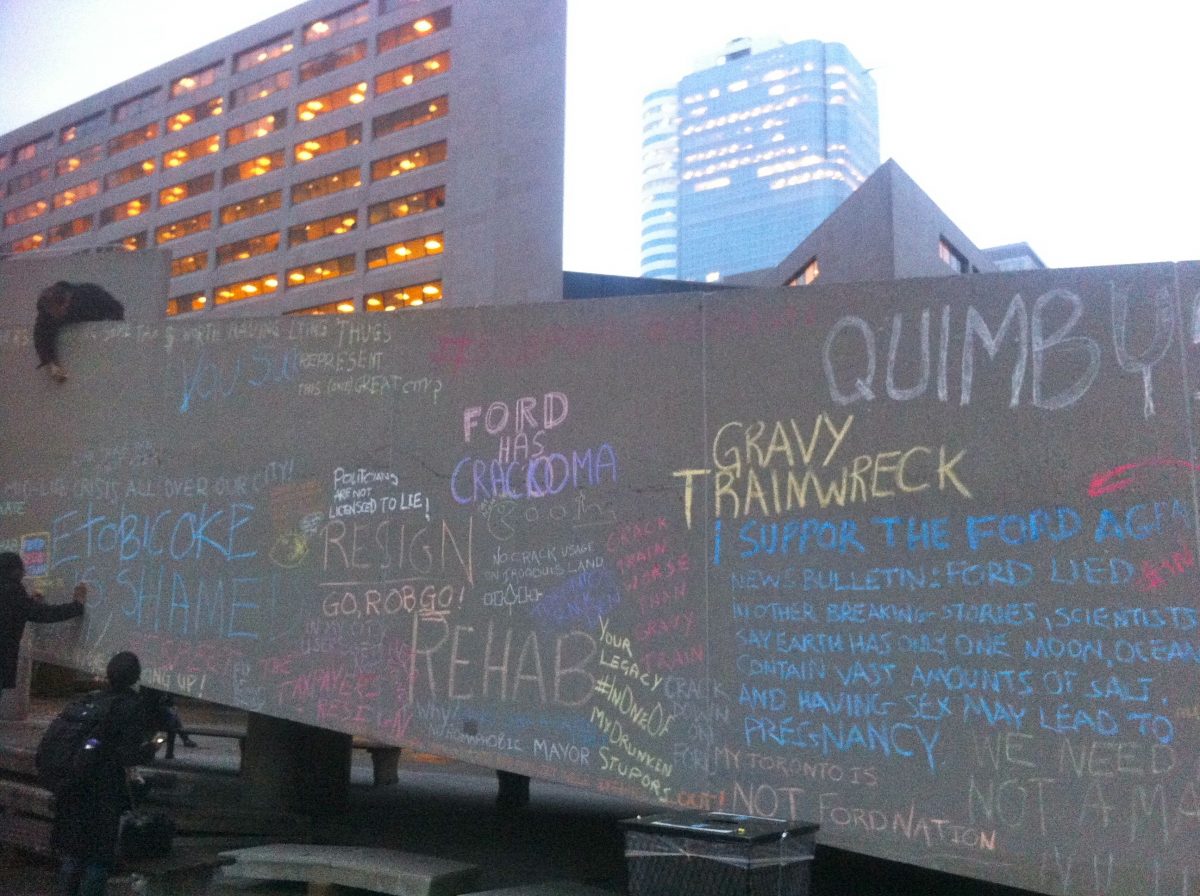

The recent scandal involving the Mayor of Toronto (Rob Ford) has catalyzed many conversations around the delineation of a person’s professional life vs. their personal life. On the Friday, November 8, 2013 edition of “The Current” on CBC Radio 1, panelists discussed their opinions around whether a public figure like a mayor can still do the job when their personal life is in such disarray.

Mayors are public figures. As leaders in society, do we believe they should be modelling the characteristics of good citizenship we would like to see in everyone? Is it okay for a mayor to admit to illegal activity, yet still act as a leader for a major world city?

In K-12 public education, teachers and principals are subject to similar scrutiny of their public lives. On Friday, an educator said to me, “Oh I would never be on Twitter. I don’t want to get fired”. It was an odd comment for me, because I have gained so, so much on a professional level from my interactions and conversations on Twitter and other social media.

As I looked for more writing on the topic, I came across Brandon Grasley’s recent post on the question, and some work by George Couros on the same topic. It is worth reading both explorations of the topic, and the comments from the many educators who have weighed in.

But the examination of personal and professional lives of School Principals goes beyond considering reputation and public activity. One of the key capacities of a school leader is to build relationships.

![]()

Building relationships is critical to the success of a School Leader. It’s also a very tricky role, particularly in communities where a School Leader may wear many other hats outside of the school building. Family members may attend the school. Staff members may be relatives or friends.

It’s even trickier when concerns arise about the performance of a staff member in the school. While we always want to “build the new”, we can’t stand by and watch when the “old” is harming the learning of students.

School leaders are trained in how to keep their professional role of leading the instructional program in a school separate from their personal lives.

Unfortunately, not all people working in a school have had the opportunity to build the capacity to accept constructive criticism of their professional practice and separate it from their personal relationships.

Leadership is not a popularity contest. School leaders are not hired to make friends, but to build relationships that will benefit the students and improve student learning, all student learning.

It takes courage, but school and system leaders must take action even when it might be interpreted as personal. They must model the change they want to see.

Is it too much to ask all of our leaders to lead by example?